By Deszure Thomas

Pairs of denim jeans and white T-shirts lined the Schuster Walkway on Lehman College’s campus. Each piece of clothing carried handwritten messages. One shirt read in bold letters, “Don’t be ashamed of your story.” A pair of jeans declared, “She’s someone’s daughter, wife, sister, niece.” Another read, “Rapists rape people! Not outfits.”

Members of Lehman’s Veterans Club stood nearby, handing out denim pins with QR codes to students. Among them was Jessica Adames. “It started in Italy, 1993,” Adames began, recounting the haunting case behind the display. “A young woman, just 18, was picked up by her 45-year-old driving instructor for her first lesson. He drove her to a deserted area and sexually assaulted her. He was convicted and served four years of his sentence before appealing. He won the appeal and was released.”

The reason? What became known as “the jeans alibi.” Italy’s Supreme Court judges argued, “Her jeans were tight, so she must have taken them off herself, and therefore it was not rape—it was consent.” Adames explained how women in the Italian Parliament protested in solidarity with the victim by wearing jeans. “They wore denim on the floor and on the steps,” she said. “This was to bring awareness that rape is rape, and consent is consent.”

The protest resonated globally. In 1999, a California senator brought the story to the United States, sparking what is now known as Denim Day—an annual April event where people wear denim to stand with assault survivors and raise awareness about sexual violence.

Fashion as Advocacy

Denim Day is one example of how fashion intersects with politics through advocacy. Throughout history, fashion has been both self-expression and resistance.

- Flapper fashion of the women’s liberation movement symbolized independence and bodily autonomy.

- Black dandyism of the 20th century challenged racist stereotypes, embracing individuality, dignity, and luxury.

When fighting oppression, fashion often becomes a weapon—challenging norms, reshaping culture, and redefining identity. With such influence, one question lingers: Is fashion political?

For many designers, models, and experts, the answer is simple: yes.

Lehman alumna and professor Giulia Baldoni, who teaches the course Black Talents and Voices in Fashion, explains. “Fashion is inherently political because politics deals with people, and people make use of fashion,” says Baldoni. “Every purchase is political.”

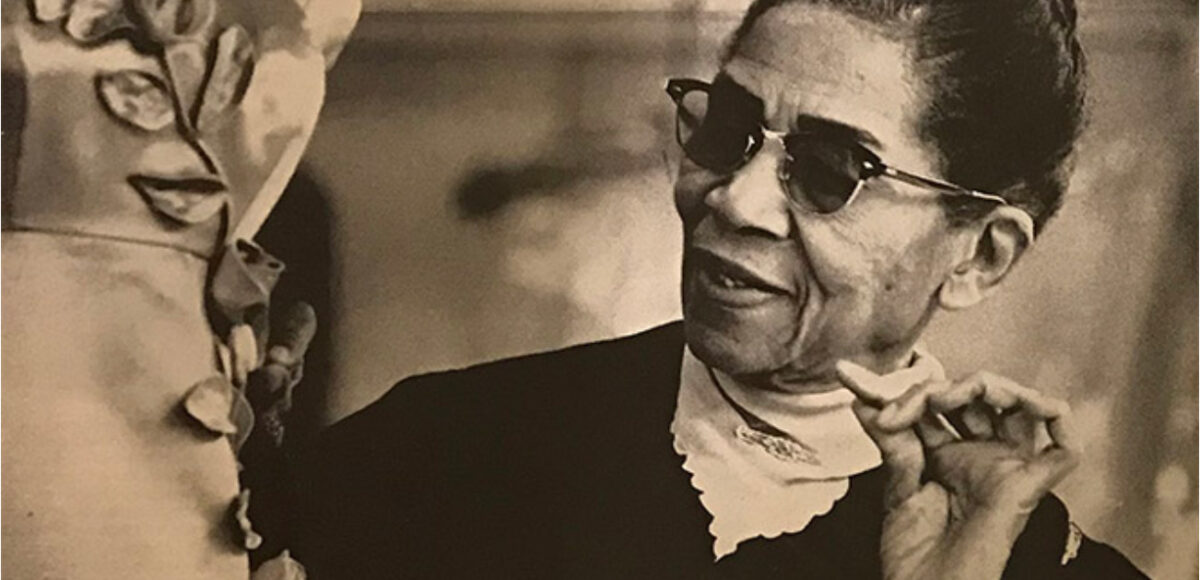

Designer Ann Lowe

So what does political mean in this context? Baldoni defines it as, “Power to the people. It’s a privilege to be aware of that power, hold on to it, and embrace it in daily civic life.”

Fashion Challenges Societal Norms: Akilah

Akilah Irvin, a member of Lehman’s Modeling Club, reflects on her experience as a Black, plus-size model.

“Being Black and plus-size in fashion is inherently political because it challenges both Eurocentric beauty standards and the industry’s obsession with thinness,” says Irvin.

Inspired by her mother’s confidence and style, Akilah emphasizes the pressures many young Black women face. “From a young age, Black women—especially plus-size Black women—are told to shrink themselves physically, aesthetically, even in presence,” she says. “The pressure to conform shows up in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.”

She notes that plus-size Black women often face limited clothing options and are discouraged from bold fashion choices. “It is important to defy these standards because visibility creates change. When plus-size Black women take up space—whether in fashion, media, or everyday life—it forces industries to acknowledge we exist, we thrive, and we deserve representation.”

Her message is one of boldness and visibility: “Being plus-size isn’t something to hide, it’s something to celebrate. Fashion is about owning your space and expressing yourself unapologetically.”

Akilah’s stance echoes iconic figures like Angela Davis of the Black Panther Party, who wore her natural afro as a political statement against Eurocentric standards. “Davis’s hairstyle is one of many testimonies to the message ‘Black is Beautiful,’” says Baldoni.

At the time, Black women were expected to straighten their hair for acceptance. Davis’s afro rejected assimilation and declared: Black women are beautiful as they are.

Baldoni adds, “While DEI is under attack, recognizing the diversity in workplaces, schools, and public spaces can empower us to show who we are—starting with our bodies, our hairstyles, and our care practices.”

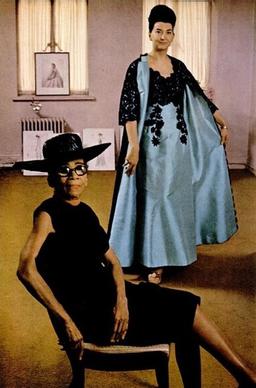

A dress designed by Ann Lowe

Fashion Reflects Politics of the Times: Giulia

In her course, Black Talents and Voices in Fashion, Baldoni highlights overlooked contributions in fashion history—such as Ann Lowe, the Black designer who created Jacqueline Kennedy’s 1953 wedding gown. “This is a powerful example of African American talent hidden from the mainstream spotlight,” Baldoni explains.

Born in 1898, Lowe learned dressmaking from her mother and grandmother, who sewed for wealthy White families. Despite segregation, she pursued couture design, eventually creating Jackie Kennedy’s wedding gown. Ten days before the wedding, a pipe leak destroyed the gowns, forcing Lowe to remake them at great personal expense. When delivering the dresses, she was told to use the back door. Lowe refused, declaring, “I’ll take the dresses back,” and marched through the front entrance.

Though the gown was celebrated, Kennedy never publicly credited Lowe. “The dress wasn’t extraordinary as a protest piece, but its erasure shows how race and gender politics shaped recognition,” Baldoni says. This moment, occurring just before the Civil Rights Era, reflected the normalization of Jim Crow and segregation. “When we talk about Mrs. Kennedy’s gown, we’re talking mere decades ago,” Baldoni stresses. “The lack of recognition for Black talent is alarming. Choosing to remember who really created these works is itself political.”

Jackie Kennedy’s wedding

Fashion and the Environment: Danelli

Fashion’s role in politics isn’t limited to advocacy and identity—it also extends to environmental activism.

Lehman senior and designer Danelli Lora builds her work around sustainability. “Even though my designs don’t always revolve around politics, sustainability is a political issue. I make every design with that in mind.”

She notes the wastefulness of fast fashion: “Brands like Fashion Nova, Shein, Rainbow, and others sell low-quality clothing that harms the environment. Depending on where people live, affordability drives them to these stores, perpetuating the cycle.”

Committed to sustainable practices, Lora cuts fabric to minimize waste and even incorporates recycled materials. Her 2021 piece Mother Nature embodied this philosophy: a floor-length gown with green leaves made from plastic water bottles, brown roots at the hem, and blooming flowers throughout.

“I wanted to show how we can all blossom if we do our part,” she said.

From Denim Day to Angela Davis, from Ann Lowe’s erased legacy to Danelli Lora’s eco-designs, fashion consistently reflects—and reshapes—politics.

Whether as protest, defiance, sustainability, or representation, fashion remains inseparable from political life. As Baldoni and others affirm: yes, fashion is political.