Promoting Unity through Advocacy, Literature, and Prayer

By Amen Dilawar

Stacks of stories and boxes of magazines, their pages yellowed and fragile, line the corners of the home of Tahira Naqvi. They are wrapped in both memory and loss.

Naqvi, a prolific writer, translator, and Clinical Professor of Urdu Language and Literature at New York University (NYU), says she wanted to tell the story of Pakistan—of Lahore. “The Lahore that I knew, the Lahore that it had become,” she says. “And then I started reading about the persecution of Christians.”

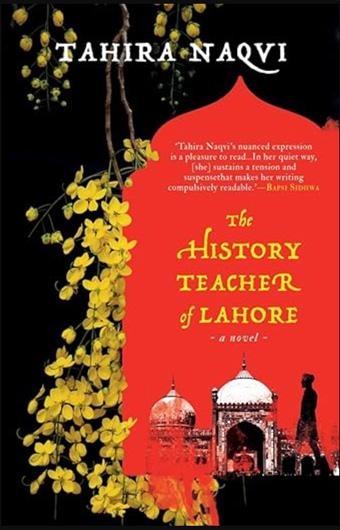

The result, The History Teacher of Lahore, is a novel about religious intolerance and sectarian violence.

Naqvi had spent her formative years in Lahore, Pakistan, at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, a school run largely by Anglo-Indian teachers or daughters of colonial entanglement who, neither fully British nor wholly accepted by local communities, formulated their own identity in post-Raj Pakistan. They wore frocks, spoke polished English, and adhered to Western customs, standing out in post-Raj Pakistan as both insiders and outsiders.

Among them was Mother Andrew, a brilliant and highly competent nun who cultivated generations of writers, politicians, and artists, including Syeda Abida Hussain and Shamim Hilaly. Together, they became known as “Andy’s Girls.” She also shaped Prof. Naqvi’s intellectual and moral imagination, which she continues to employ in her masterfully crafted novels and translations of works by literary giants such as Saadat Hasan Manto, Khadija Mastur, Hajra Masroor, and most extensively, Ismat Chughtai, whose fierce, feminist, and politically charged stories she has rendered with literary elegance.

Among them was Mother Andrew, a brilliant and highly competent nun who cultivated generations of writers, politicians, and artists, including Syeda Abida Hussain and Shamim Hilaly. Together, they became known as “Andy’s Girls.” She also shaped Prof. Naqvi’s intellectual and moral imagination, which she continues to employ in her masterfully crafted novels and translations of works by literary giants such as Saadat Hasan Manto, Khadija Mastur, Hajra Masroor, and most extensively, Ismat Chughtai, whose fierce, feminist, and politically charged stories she has rendered with literary elegance.

“I remember that I used to go see Mother Andrew and that is when persecution was at its height,” she recalled. “Terrible things were happening with the blasphemy law. Asma Jahangir, a renowned lawyer and human rights activist, became an important person in supporting cases for persecuted Christians. When I went to see Mother, she was also with us but junior by many years than me. Mother said, ‘When one of them dies, they become martyrs. But when one of us dies, it is just like oh, a Christian was killed. And then she said, ‘Oh my Asma, my Asma, I am proud of you for defending our people.’”

The persecution of Christians in Pakistan intensified during the regime of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Waves of fear followed due to blasphemy allegations, mob violence, and the slow erosion of coexistence. Under his campaign of Islamization, society’s notions of diversity and what it meant to be a “good Muslim” distorted dangerously. “People became very conscious of their own sense of superiority as Muslims,” said Naqvi.

This distorted perspective in the name of “Islam” is portrayed in The History Teacher of Lahore when Arif raises his voice and says:

“Young people like you have to unlearn the lessons taught by leaders who, like Aurangzeb, thought Islam was any one sect’s personal property. Islam is not only for all Muslims, it is for anyone who wishes to be a part of it. Do you know the ayat in the Quran, ‘Let there be no compulsion in religion, truth stands out clear from error, whoever rejects evil and believes in God hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And God heareth and knoweth all things?’ Does this ayat say anything about distinguishing between Sunni and Shia? Or persecuting members of other religions, like Christianity?” (The History Teacher of Lahore, p. 202).

As new blasphemy laws were passed and older ones more strictly enforced, the idea began to circulate that Christians posed a hidden threat—people who might one day defile the Quran, insult the Prophet, or violate sacred boundaries. People did not realize that many of these laws were not derived from the Quran at all. Yet, over time, these anxieties calcified into action. Christians were no longer viewed as fellow citizens. They were watched closely, spoken of cautiously, and eventually, hunted.

Some of the most horrifying cases illustrate this shift from suspicion to violence. For instance:

- In 1997, a mob destroyed hundreds of Christian homes and churches in Shanti Nagar after rumors of Quran desecration.

- In 2002, gunmen stormed the office of Christian charity Idara-e-Amn-o-Insaf in Karachi and executed seven staff members.

- In 2009, in Gojra, eight Christians—including women and children—were burned alive by a mob.

- In 2013, suicide bombers attacked All Saints Church in Peshawar, killing over 80 worshippers.

- In 2014, Shama and Shahzad Masih were burned alive in a brick kiln after a blasphemy accusation.

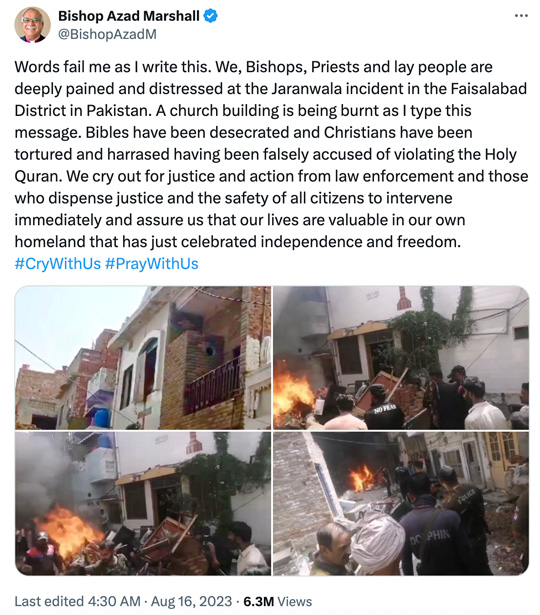

- In 2023, in Jaranwala, over 20 churches were vandalized, 80 homes torched, and families forced to flee over an unverified Quran desecration claim.

According to International Christian Concern, “At least 20 Christians languish in Pakistani prisons on blasphemy charges, collectively serving more than 134 years for crimes they did not commit.”

This pattern is not confined solely to Pakistan. In Nigeria, thousands of Christians have been killed by Boko Haram and Fulani extremists. In North Korea, Christians are executed or imprisoned for simply owning a Bible. In Eritrea, believers worship underground to avoid torture. In India, pastors are beaten and churches razed under impunity.

Consequently, Prof. Naqvi began writing. She took actual incidents and wove them into the fabric of fiction: “The novel was an allegory of Pakistan… where a time of innocence and great promise shattered.”

In The History Teacher of Lahore, Arif Ali, a young idealist, refuses to teach propaganda in a far-right Pakistan. Amid rising intolerance, he risks his life to save a falsely accused student. Prof. Naqvi deliberately uses a Muslim man to defend a Christian boy—not out of religious obligation, but human decency. “It’s a question of humanity, and I think we have lately lost it,” she said.

According to the 2025 Open Doors World Watch List, more than 4,100 Christians were killed and 3,300 kidnapped in Nigeria in the past year alone. Eight of the 10 deadliest countries for Christians are in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Russian-occupied Ukraine, 67 clergy members have been killed since 2022. Open Doors also reports over 360 million Christians face severe persecution globally. In India, 1,629 were detained without trial in the past year. These aren’t just statistics—they are stories of loss, faith, and courage.

In Plateau State, Nigeria, entire Christian villages are incinerated while officials look away. A Wall Street Journal exposé labeled it “religious cleansing.”

Persecution is not limited to violence. Open Doors defines it as any hostility toward someone identifying with Christ, including discrimination, marginalization, and injustice. The 2025 Global Prayer Guide by The Voice of the Martyrs, an international nonprofit whose mission is to defend the human rights of persecuted Christians, names 30+ countries as “Hostile” to Christians, including Bangladesh, Colombia, Ethiopia, and Israel. The top 10 countries where persecution is most severe: North Korea, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Sudan, Eritrea, Nigeria, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan.

PEN America’s Manager of Research and Advocacy for the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center, Anh-Thu Vo, noted parallels in global censorship: “I’ve worked on cases involving Vietnamese writers like Pham Doan Trang, targeted for exposing systemic injustices, and have done research on social media and the Rohingya genocide. State censorship and hate speech—spread both through traditional media and social platforms—were weaponized to dehumanize the Rohingya, incite violence, and justify atrocities. State censorship acts as a tool to control narratives, suppress dissent, and deepen ethnic or communal divisions.”

In this polarized world, the only way to achieve unity is through collective advocacy and spoken truth expressed through writing. This type of literary resistance exposes what regimes try to erase. “Writers are the chroniclers of truth, culture, and identity… words hold the power to unite and inspire,” Vo said.

Prof. Naqvi reinforced this: “Poetry is a way of rebelling… A lot of poetry Arif writes is about rebellion, discontent, and revolution.” In her novel, she uses a quote from Tertullian:

“‘If the Tiber rises too high or the Nile too low, the remedy is always feeding Christians to the lions.’”

A satirical critique of scapegoating marginalized groups.

Oluomachukwu Anude, a Nigerian and leader in the VOM student fellowship, emphasized prayer as action: “‘Every Wednesday, students gather to pray for a specific region of the global Church facing persecution. In partnership with VOM’s mission, we are calling the Western Church—especially our generation—into true solidarity with the suffering Body of Christ. Solidarity moves beyond sympathy. It is intercession born of empathy, praying as if we ourselves were in chains. It is a sacred privilege to join our Great High Priest, Jesus, in standing in the gap for His bride.’”

Anh-Thu Vo also mentioned, “Advocacy is a cumulative process… Every conversation, no matter how small, plants a seed that could grow into meaningful change later.”

Prof. Naqvi urged education as defense against cruelty cloaked in the guise of faith: “How many of those persecuting Christians know what the Quran actually says?”

An excerpt from The History Teacher of Lahore reads:

“‘Why are you afraid, write fearlessly

Write a chapter of truth with your pen,

Write of the shores lying within the storms

It is not right to remain silent in the face of brutality,

Write the reckoning of this life on the tablet of the world.’” (p. 236)

Lastly, for Prof. Naqvi, writing and translation (akin to poetry) are not merely artistic pursuits but acts of resistance, since even the softest voice can pierce through the voice of oppression and awaken something human in those who listen. “Translation is a very freeing and intimate process for me. I feel as if I have found my way into another world. For my most recent novel, The Cry of the Nightingale, comes from a couplet by the famous classical Urdu and Persian poet Mirza Ghalib. This is how the couplet would be translated by me: ‘Who says that the lament of the nightingale is in vain. Within the folds of the rose, a thousand hearts were shattered.’ The idea is that if you cry out, lament, and protest, it is not in vain because it will touch somebody. Somebody will hear it,” said Prof. Naqvi.

Below is a prayer for families of martyrs by The Voice of the Martyrs:

Dear Heavenly Father,

Thank you for the example of persecuted Christians who remained obedient…

Please give these widows and orphans a supernatural ability to forgive and, in that forgiveness, to proclaim your goodness.

May they receive every need…

In Jesus’ name, Amen.

Thank you, Father, for comforting the brokenhearted and blessing those who mourn. Thank you, Father, for unity in the global body of Christ. In Jesus’ name, Amen.