By Amen Dilawar

Book censorship has long been a mirror to humanity’s fears, power struggles, and shifting values. Across centuries, the suppression of books has often been about more than just words on a page—it’s been a means of obtaining dominion over thought, shaping ideologies, and enforcing conformity. Whether through bonfires in ancient Ephesus or political crackdowns in modern regimes, censorship reveals what societies are most afraid to confront.

One of the most prominent examples of institutionalized censorship comes from the Roman Catholic Church. For nearly 400 years, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books) served as the Church’s tool for regulating what Catholics could read. The Index was not merely a list of obscure texts because some of Western literature’s masterpieces found their place on this blacklist considering that they were deemed dangerous to the faith.

Beginning in the 16th century and continuing until 1966, it cataloged over 4,000 books, spanning religious texts to works by intellectual giants. Its origins, however, reach back to Apostolic times when early Christians sought to purge superstitious writings. What started as bonfires of “undesirable” volumes turned into an institutional practice of dictating which ideas were worthy of dissemination and which deserved suppression.

While religious censorship like the Index transpired in the 20th century, the battle over intellectual freedom remains to be fought even today, and history depicts that the fight against censorship is as long-lasting as censorship itself. It is, however, imperative to note that religious authorities are not the only ones to fear the written word. Totalitarian regimes have long wielded censorship to maintain power and suppress dissent. The Soviet Union under Stalin provides a major example. While state censorship sought to erase dissenting voices, the underground literary network known as samizdat resisted. Writers reproduced banned texts by hand or typewriter and risked imprisonment to preserve ideas deemed threatening to the regime.

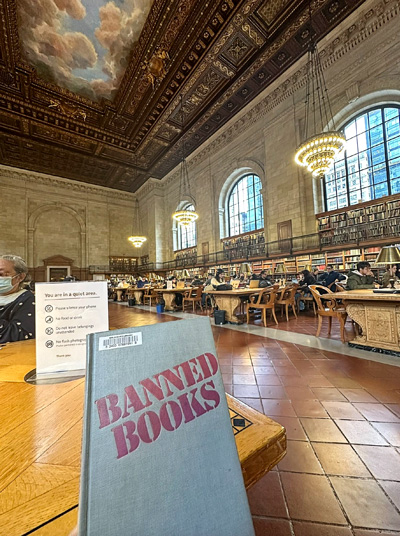

As noted in the book Banned Books 387 B.C to 1978 A.D. by Anne Lyon Haight and Chandler B. Grannis, the United States, often seen as a promoter of free speech, has its own history of censorship. In the 1950s, at the height of Cold War paranoia, the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) faced backlash for purging books from overseas libraries. Tasked with presenting America’s ideals to the world, these libraries found themselves scrutinized by Senator Joseph McCarthy, who claimed they housed pro-Communist literature. The result was a hasty removal of over 40 authors’ works, prompting debates about whether censorship undermined the very freedoms the U.S. sought to promote.

As noted in the book Banned Books 387 B.C to 1978 A.D. by Anne Lyon Haight and Chandler B. Grannis, the United States, often seen as a promoter of free speech, has its own history of censorship. In the 1950s, at the height of Cold War paranoia, the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) faced backlash for purging books from overseas libraries. Tasked with presenting America’s ideals to the world, these libraries found themselves scrutinized by Senator Joseph McCarthy, who claimed they housed pro-Communist literature. The result was a hasty removal of over 40 authors’ works, prompting debates about whether censorship undermined the very freedoms the U.S. sought to promote.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower later addressed these tensions, famously denouncing book burning and urging Americans to confront opposing ideologies through understanding rather than suppression. However, contradictions lingered. Even as Eisenhower spoke out against censorship, government policies continued to restrict books abroad, with titles like James Baldwin’s Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone and William J. Lederer’s The Ugly American excluded from USIA libraries for their critical perspectives on American society.

Domestically, censorship took on its own flavor, often shaped by local controversies. Libraries and schools became battlegrounds where community values clashed with intellectual freedom. In 1951, authorities in Dubuque, Iowa, raided the public library, seizing classics like The Decameron as obscene. In Oklahoma, a librarian was fired for defending the inclusion of magazines addressing race relations. Even major institutions like the Boston Public Library faced attacks for holding Communist literature, though it was confined to reference collections.

Another relevant case in point is when in El Paso, Texas, a history textbook was banned in 1954 for reprinting the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights alongside the Declaration of Independence. Critics argued that such inclusions promoted internationalist views at odds with patriotic education. Meanwhile, Frank Magruder’s American Government faced widespread attacks for its perceived support of the United Nations.

Akin to modern day, we see similar debates rebranded in disputes over “sensitive material” in libraries and classrooms. As made evident by The American Library Association (ALA), it documented efforts to censor 4,240 unique book titles in schools and libraries in 2023, a 65% increase from 2022 and the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago. This surge in book bans in the United States is still incredibly prevalent, specifically in public schools in New York City. For instance, PEN America, an organization dedicated to defending free speech and the organization that I have worked with for the past four years, has documented over 10,000 instances of book bans during the 2023-2024 school year in public schools across the country. These bans disproportionately target books written by authors of color, LGBTQ+ authors, women, and those addressing themes such as racism, sexuality, gender, and history. The rise in censorship is not just about restricting literature but also about silencing marginalized voices and excluding narratives that challenge dominant ideologies.

Since 2021, this alarming trend has escalated substantially over time. With reports of book bans in 29 states and 220 school districts, states like Florida and Iowa have taken the lead in implementing such restrictions. For example, over 40 percent of all book bans occurred in school districts in Florida. Across 33 school districts, PEN America recorded 1,406 book ban cases in Florida, followed by 625 bans in Texas, 333 bans in Missouri, 281 bans in Utah, and 186 bans in Pennsylvania. The high concentration of bans in certain states suggests a coordinated or policy-driven approach to restricting educational content.

The discriminatory nature of these initiatives is proven by the fact that 44% of the most often banned books during the 2023–2024 school year contained characters or persons of color, and 39% featured LGBTQ+ characters or themes. The implications of these bans extend far beyond individual books or authors. Literature has always served as a fundamental tool for education and personal growth that also offers both a mirror for readers to see themselves and a window into the lives of others. By restricting access to diverse stories, book bans undermine students’ ability to develop empathy, critical thinking, and a wider understanding of the world. PEN America views this fight as a defense of democracy, inclusion, and the fundamental right to access information.

In 2024, between January 1 and August 31, 2024, ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom tracked 414 attempts to censor library materials and services. In those cases, 1,128 unique titles were challenged. In the same reporting period last year, ALA tracked 695 attempts with 1,915 unique titles challenged. Though the number of reports to date has declined in 2024, the number of documented attempts to censor books continues to far exceed the numbers prior to 2020. Additionally, instances of soft censorship, where books are purchased but placed in restricted areas, not used in library displays, or otherwise hidden or kept off limits due to fear of challenges illustrate the impact of organized censorship campaigns on students’ and readers’ freedom to read.

In some circumstances, books have been preemptively excluded from library collections, taken off the shelves before they are banned, or not purchased for library collections in the first place. Moreover, as covered in the “America’s Censored Classrooms 2024” report published by PEN America, in 2024, state governments enacted eight bills or policies that PEN America defines as educational gag orders—direct restrictions on educational speech in the classroom. State governments also enacted five additional higher education bills that endanger academic freedom in ways that are not direct censorship, such as politicization of university governance; bans on diversity, equity, and inclusion; and restrictions on faculty tenure. In all, 47 educational gag orders and 10 other higher ed restrictions were enacted in 23 states between January 1, 2021, and October 1, 2024. This aligns with the notion of a systematic effort in place to regulate and constrain educational discourse.

Q & A with Dr. Jonathan Friedman

Friedman is a distinguished scholar, advocate, and leader in the fight for free expression and academic freedom as well as his team members at PEN America, an international human rights organization that upholds press freedom worldwide.

Q: What drives your as well other advocates’ passion for protecting literary freedom?

A: Since 1922, PEN America has been passionate about defending literary freedom because this freedom is constantly under threat. Many of PEN’s members and staff are writers themselves, so they/we understand how important the right to express oneself freely is. All people should have the freedom to write, read, and receive information.

Q: What long-term impacts might these censorship efforts have on free expression and the intellectual growth of future generations?

A: Banning the expression of certain ideas (for instance, the recent spate of laws banning various aspects of DEI in state universities) is banning knowledge, so in addition to restricting free speech now, these censorship efforts can hamper the circulation of knowledge for future generations. This dynamic is especially problematic when considering that much of the books, stories, and academic teaching being targeted by politicians centers on gender, sexuality, and racism, much of it written by people of color and LGBTQ+ people. Stories matter. What we tell ourselves and show others about our past, present and future builds community and identity, shapes understanding and supports empathy. When those stories are removed and are banned, our young people lose opportunity and capacity to grow. That can be devastating to our students, especially given how many today live in families whose identities were historically banned from the mainstream of American culture. Public schools and libraries are where many young people encounter such diverse stories and representations.

Q: What factors have contributed to the rise in educational censorship? And how do these book bans intersect with other forms of censorship?

A: Since 2020, a range of conservative legislators have found educational censorship to be an effective tool for rallying their base to fight against so-called progressive or “woke” ideas, which has resulted in numerous state laws restricting books and restricting discussion of certain topics (most notably related to DEI, as mentioned above) on college campuses, or in schools. Our recent America’s Censored Classrooms report gives a good overview of these censorship trends over the past few years, beginning in 2020.

Q: How has PEN America’s role in documenting and challenging book bans evolved since this issue began to escalate? What steps have been taken to combat this issue?

A: To help keep up with the growing number of bans–more than 10,000 in the 2023-24 school year–we have added staff to help document these bans and we have increased our efforts to work with local groups who fight book bans such as the Florida Freedom to Read Project. We have primarily focused on combating the issue by raising public awareness of it via our research, but we have also taken legal action against the book bans in Escambia County, Florida.

Q: What role should educators play in resisting censorship while tackling potential professional risks?

A: Educators should not censor what they teach or what materials they have available in their classrooms unless absolutely forced to do so. In other words, they should not do the censors’ work by self-censoring in anticipation of potential censorship efforts or threats. Depending on risk and personal situation, educators can also document changes they or their colleagues are asked to make to comply with legislation. They can reach out confidentially to places like PEN America if they have concerns about how laws might be applied in their library or school. Reporting book bans informs PEN America’s research and advocacy efforts.

Q: In your experience, are there books that are preemptively excluded by schools or libraries due to the mere fear of backlash, even without formal bans?

A: Yes, many of the large-scale district bans (i.e., where a school district bans 100 or more books at once) we have seen in states such as Florida and Iowa remove books that might run afoul of vague censorship laws without the books being formally challenged. We also believe that many school districts now choose not to buy books that have been banned elsewhere, though it is impossible to document such “soft censorship” definitively.

Q: How can people, especially those who may not directly experience the effects of book bans, be inspired to join the fight for literary freedom?

A: There are many ways. The first step anyone can take right now is to thank their librarians and educators for the work they do in their community. And try to do so publicly – at a meeting, in a newspaper, in a statement to the school. This demonstrates something important. Most people don’t like people telling them what they can and cannot read. Most folks trust librarians and their teachers. Reinforcing this publicly and positively builds a stronger community for when – and increasingly, not if – censorship efforts come to their neighborhood. People can also go to their local school board meetings to speak out against any book bans that might be proposed there. They can write letters to the editor in areas where bans are proposed or have occurred.

They can get involved with local organizations fighting censorship or national organizations such as PEN America, the National Coalition Against Censorship, EveryLibrary, and others. If they have the funds, they can buy books that have been banned to read for themselves or to distribute in their communities (for instance, via Little Free Libraries).

Furthermore, participating in events like Banned Books Week is an effective way to celebrate the freedom to read. Organizing local readings, discussions, or displays featuring censored materials can bring visibility to the issue. Defending controversial books during challenges at school boards or library meetings is essential, as is writing letters to officials or editors to explain why access to these materials matters. Therefore, the Library Bill of Rights, adopted by the American Library Association in 1948, remains a guiding document for resisting censorship. It asserts that libraries must provide access to diverse viewpoints, regardless of political, religious, or social pressures. By upholding the right to information, libraries serve as protectors of democracy and make sure that individuals can engage in all forms of informational exchange. Hence, it’s crucial we comprehend that book banning is an attempt to not only regulate the narrative being circulated but rule over the minds, knowledge, and futures of individuals.

No comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.