By Adrian Currie

“It’s a pattern of behavior where one intimate partner coerces, dominates, and isolates the other intimate partner in order to maintain power and control over the partner and over the relationship.”

New York City’s Family Justice Centers (FJCs) support victims and survivors of domestic and gender-based violence. The organization also trains workers in other city agencies about issues involving intimate partner violence.

Angela Inglis, director of programs and community partnerships at the Bronx Family Justice Center explained the purpose of the Family Justice Centers in a February training session. “Our whole mission for being is to support survivors of intimate partner violence, of gender-based violence, people who are experiencing relationship violence and abuse,” she said. Family Justice Centers are operated by the Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence (ENDGBV).

Angela Ingris

The FJC training covered what happens when law enforcement shows up on the scene of possible intimate partner violence. Ingris highlighted the importance of law enforcement evaluating the circumstances upon arrival to a domestic dispute.

“Sometimes it can be really hard to know and to determine what that [relationship violence and abuse] looks like,” says Ingris. “When police show up at a scene and somebody has marks on their arms, because someone has grabbed their arms…But what happened before that struggle?”

Angela Ingris

The “In-Depth Assessment of Criminalized Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence” training was aimed at professionals who work with domestic abuse victims and survivors. The focus was how to have effective conversations during the initial assessment of a possible victim of domestic violence.

Marian Miller, a trainer and clinical advocate with the Criminalized Survivors program at STEPS and Family Violence, discussed some of the reasons why assessment is important when interviewing survivors of intimate partner abuse. She said the training was created after it became clear that some service providers were “really struggling with how to have some of the conversations around what violence or abuse might look like for folks that they’re supporting.”

STEPS is a holistic program under the nonprofit Rising Ground that provides services for intimate partner violence (IPV) and gender-based violence survivors.

Group facilitators asked the group to state reasons for assessing new clients, which included curiosity, safety concerns, finding out if there’s been a pattern violent behavior and possibly what survivors have done previously to get through intimate partner violence. “It’s a way to better understand a survivor’s history,” said Soraya Palmer, another trainer.

Soraya Palmer

Jessamy Klapper, a social worker with Pillars of Peace, said curiosity was important. “It’s important to acknowledge that that’s a natural response to have sometimes,” said Klapper. “You’re bringing curiosity to places where there might otherwise be judgment or assumption. There are places where curiosity, a kind of gentle curiosity, can be helpful.”

Jassamy Klapper

Palmer explained that intimate partner violence is “a pattern of behavior where one intimate partner coerces, dominates, and isolates the other intimate partner in order to maintain power and control over the partner and over the relationship.” She suggested a few questions people can use to determine whether a pattern of abusive behavior exists. “Has this ever happened before and, if it did happen, what was that like?” she said. She said it was important to recognize that people’s relationships ebb and flow potentially. “If IPV is present, it generally isn’t gonna start on day one of a relationship, and it might escalate over time. So, what was the relationship like at the beginning? What were the things that drew you to this type of behavior to start happening?”

Soraya Palmer

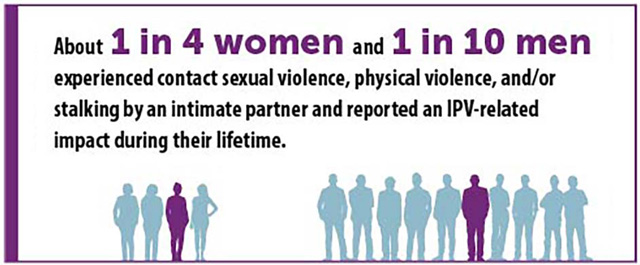

“About 1 in 4 women (25.1% or 30 million) in the U.S. experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime and reported some form of IPV-related impact,” according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), an ongoing survey developed by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and first collected in 2010. As for men, “Nearly 1 in 10 (10.9% or 12.1 million)” experienced the same.

Other questions Palmer cites in assessing clients for IPV are, “Has your partner used physical violence? Have you used physical violence and has this gotten worse?” These questions are important, because they “get the person to think about the behaviors that their abusive partner used,” said Palmer.

“They will use those behaviors for different reasons and with a different impact, potentially, because the power dynamics impact if IPV is present… to try and fight back or protect themselves. But if we’re not asking to make some of those distinctions or asking about both people’s behaviors, we’re gonna miss some of what’s going on.”

Wednesday’s training focused primarily on intimate partner violence. But, gender-based violence can include family violence, sexual assault. elder abuse, stalking, and human trafficking.

The group covered two case studies at the end of the training, in which participants were asked to comment and answer certain questions.

The first study involved a 23-year-old named Ezra who had two prior arrests, for prostitution and assault. Ezra has an order of protection against them, and a former partner once “sought medical attention because of injuries Ezra caused.” Ezra must complete a court-ordered anger management course and wants to know “if your program has anger management.” The question is, “How do you approach Ezra’s service goals?”

Some of the group’s responses included fully assessing Ezra to see if they have a history of violent abuse themselves, whether anger management is the best program for them, and whether they are genuinely interested in the program or are simply trying to avoid jail time. Other responses were asking Ezra more questions to find if their prostitution charges are related to something more, such as trafficking, and if they’re the actual aggressor in the circumstances.

Because Ezra is masculine presenting, one participant suggested that Ezra’s appearance might’ve incorrectly placed them as the aggressor and that getting more details from them could be useful. Another suggest that assuming Ezra is the bad person because of their court order might not be wise.

In the second case study, Amelia, a 21-year-old woman facing an accessory charge of “assisting in the sexual assault of another woman,” tells you, the social worker, that she was unaware of an assault in progress while she and her partner were at the partner’s friend’s house where the assault took place. She says she only became aware when she saw the woman leave in a panic.

You find out from another service provider after your first meeting with Amelia that she, a co-defendant on the case, has an “extensive history of being trafficked as a teenager.” The question is, “How do you approach your second meeting with her with this new additional information?”

Palmer said it was important to explain to the client that there is no attorney-client privilege in the event the worker’s notes are subpoenaed, as one participant raised the concern of whether the other provider had permission to discuss that information with the social worker in determining if the social worker should mention Amelia’s history of being trafficked.

Another said that bringing up Amelia’s history could break the trust established with the other service provider if that provider was not supposed to share that information.

“I’d like to ask Amelia how does she feel about the other woman, to find out where her empathy may lie with that [the assault],” said another participant. “Maybe somehow it may lead into her teenage years. Maybe it can open up a conversation, or maybe it can help me to know where her mind-state may be when it comes to other victims or victims.”

One attendee suggested that perhaps Amelia and other survivors of abuse and trafficking may not identify as such or may not “put two and two together when it comes to other forms [of abuse].” Palmer said it would be important to hear how survivors describe their experience.

Family Justice Centers are located in all five boroughs and can be accessed by dialing 311. The centers also have city agencies and district attorney’s offices located on-site “to make it easier for survivors to get help.”