By Thairy Lantigua

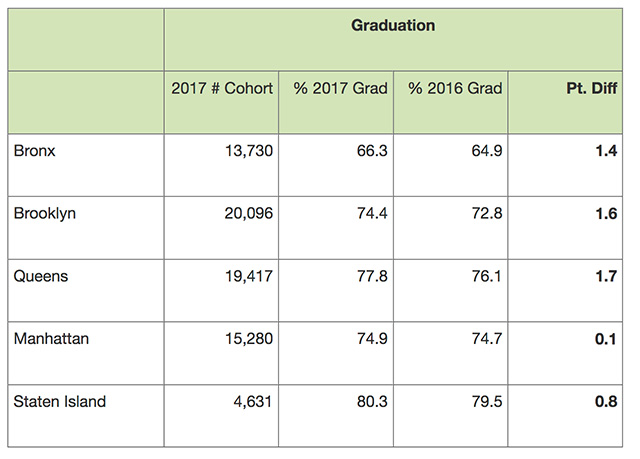

In February, the New York City Department of Education (DOE), alongside Mayor Bill De Blasio, announced a record high in graduation rates, with the dropout rate decreasing from 8.5 percent in 2016 to a 7.8 percent in 2017, the lowest it has ever been. The graduation rate rose and the dropout rate fell in every borough and among every ethnicity according to the DOE. The Bronx had the highest dropout rate at 11.7 percent, followed by Brooklyn at 7.4 percent, Manhattan at 7.3 percent, Queens at 6.4 and Staten Island at 6 percent.

For several years the Bronx has been the borough with the highest dropout rate in the city. Some of the areas with the highest dropout rates are Crotona Park, Morrisania, Melrose, with a dropout rate of 15.1 in 2017, an increase of 1.6 percent from the 13.5 rate of 2014.

Although gaps between racial and ethnic groups have decreased over the last decade, Hispanic youth are still more likely to drop out of high school than students of other major races.

By the year 2017, 10.7 percent of Latino students dropped out of high school, compared to 7.9 percent of Black students, 4.4 percent of White students and 4 percent of Asians. The dropout rate for foreign-born youth shrank from 29 percent in 2000 to 10 percent in 2016, although it remains well above the national average.

More boys drop out of school citywide. In 2017 9.2 percent of dropouts were male and 6.3 percent were female.

One reason students drop out of school is poverty, especially in the Bronx where 14.1 percent are economically disadvantaged, compared to an overall rate of 7.2 percent in New York City. Students from low-income areas are 2.4 times more likely to drop out of school than those from middle-income neighborhoods. When students have to worry about basic necessities like food, shelter, and safety, it’s harder for them to put effort and energy into school.

A significant percent say that they leave school because they were failing too many classes. About 26 percent said that they dropped out to become caregivers, and more than 20 percent said that school simply wasn’t relevant to their personal lives or achievements. Some join gangs and lose interest in education. Only a small percentage said that they drop out because of school environment, ineffective teachers, residential instability, mental health issues, or getting kicked out of school.

Will Baez, 24, who dropped out of the High School of Applied Communications in 2012, said that school didn’t have anything to offer him. “I know that many people can work in that environment but that was not my case,” said Baez. “I was constantly failing, and getting in trouble. There was no reason to go further when I clearly wasn’t going nowhere. I like what I do now and that’s what matters to me.”

While higher graduation rates is a positive development, they doesn’t necessarily mean that students are learning more or putting more effort into school. According to some working in the field of education, a few measures have made it easier for New York City students to earn a diploma.

One of the most significant changes is that students can opt out of a social studies exit exam and instead take a different test in subjects like science, math, arts or career and technical education. This change was first implemented in 2014, but over the years state officials have been adding alternative paths, including allowing students to substitute a work-readiness credential for the final exam. New York state officials announced that 9,900 students chose one of these testing or credential options in the 2017. New York City officials said that an estimated 2,000 students used one of these options.

Students can also appeal a failed exam. In previous years, students needed to score a 62 to appeal a score, but as of 2016, they can appeal a score of 60 or higher and they don’t have to submit to an attendance requirement. According to an initial analysis by the city, 1,932 students took advantage of this new appeal process.

Another change that has eased the path to graduation is that instead of passing five Regents exams, students can graduate by passing four of them and earning a credential that demonstrates they are qualified for entry-level employment. That change was in place for the 2016 graduating class, but the class of 2017 had more opportunity to use it.

“It’s understandable that several groups of students won’t like the environment but later find a subject that they like,” said Luisa Canizares, 72, a retired teacher. “We might give the students some other alternatives to engage them, but it does not mean that is to help the state reflect better numbers.”

Critics often point out that many graduates are not ready yet for college-level work. High schools are integrating programs to their curricula that will help prepare students for college. “AP for All” gives more students more access to advanced placement (AP) and preparatory courses. The DOE says that 75 percent of students were offered at least five AP classes by fall 2018. They are projecting that by fall 2021, students at all high schools will have access to a full slate of at least five AP classes, thereby increasing college and career readiness for all. The goal is that by 2026, 80 percent of students will graduate from high school on time and that two-thirds of the graduates will be college ready.

“There is a lot of research on underprepared incoming college students,” said Tracy Mejia, 31, a program assistant of College Now program at Lehman College. “In college, students need to self-advocate and accept responsibility for their actions, besides other skills such as time management and team work. Many high school students do not have these characteristics or skills.”

College Now at Lehman College is one of the programs helps students transition to college level classes. It is a free, dual-enrollment program for NYC public high school students which provides students with college-credit bearing courses taught on the Lehman College campus.

Of the 74 percent of students that graduated in New York City last year, only about 64 percent of graduates earned high enough test scores to avoid remedial classes at CUNY colleges. However that number changed this year because CUNY changed how it defines college-readiness.

The critical change was lowering the bar in math. Students can show they’re ready for entry-level college math courses in three ways: scores on the SAT, high-school performance and via a CUNY math placement exam. But CUNY loosened the standard for high-school performance. Under the prior math policy, a student had to exceed the cut-off point on any one of the three Regents math tests (Algebra 1, Geometry, Algebra 2) and pass the Algebra 2 course. Under the new policy, a student no longer has to pass Algebra 2, also known as trigonometry. Also for the first time, students who scored just below the passing cut-off score on the math-placement tests are allowed to retake the exam. As a result, the decrease in students needing remediation was largely in math, not reading and writing. The number of students requiring remedial math instruction decreased from 73 percent in the fall of 2016 to 52 percent in the fall of 2017.

Some CUNY professors believe that the readiness score shouldn’t have been lowered. They suggest that CUNY instead should keep supporting the programs they have to help the students in college. The DOE pointed out that the city’s college-readiness rate would have increased by six percentage points in 2017, without the changes that CUNY made. This is a sign, said the department, that more students are leaving high school prepared for college, not just earning diplomas. In addition, more city students are enrolling in college after they graduate, the officials noted, which is also a positive trend.