By John Breece

In Van Asher’s cluttered office at St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction in the South Bronx there is a palpable sense of urgent mission. Amid the large globefish tank with black and white frog poking out among the fish and the piles of motorcycle helmets are stacks of boxes of naloxone kits.

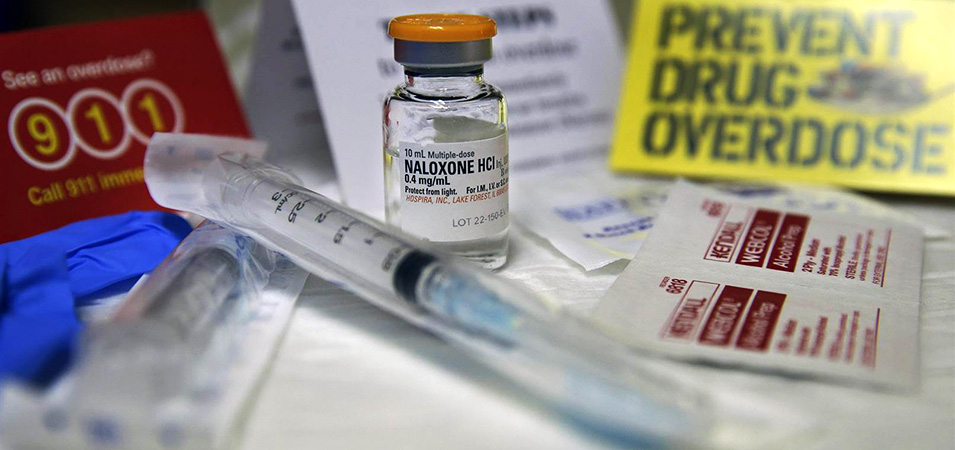

Each kit holds two doses of the emergency spray that has brought many drug users back from the nodding edge of opioid overdose, a face mask for mouth-to-mouth respiration, and blue rubber gloves. The efficient little blue pouch comes with instructions in English and Spanish on how to use its contents. This matter-of-fact packaging has become a routine fact of life for Asher, who is preparing to train 140 people in administering the emergency dosage of naloxone the next day at Fordham University.

Asher is grappling with a burgeoning health crisis where accidental overdoses have become the biggest killer of people under the age of 50. These deaths account for more losses of life than the United States suffered in the whole of the Vietnam War. The opioid overdose crisis has taken 1,374 lives in the last year alone.

The first step in turning lives around, according to Asher, is denying death. The tattooed and voluble Asher has been on the front lines of the opioid crisis for a year and a half. In his direct and immediate dealings with drug users, he encounters people with complicated issues and the urgent needs that opioid addiction brings. He is an advocate of the what-works-now, common sense approach. He engages with the people most affected by the opioid crisis and discovers what their specific needs are by listening and working with them. There is no cold, clinical remove in Asher’s approach and it reflects the overall mission of St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction.

With this direct, engaged approach, Asher is a man who has gotten a lot of pushback from the established harm reduction community. Asher doesn’t judge or pretend to a have a one-size-fits-all approach to saving lives. Each person who comes to the center for help is unique, he says, and requires a case-by-case approach.

Asher credits the de Blasio administration for allocating funds for 100,000 naloxone recovery kits and for increasing police spending to deal with the crisis. However, he believes these measures are not enough. “We criminalize people based on one behavior,” says Asher, citing a cycle of arrests and bail which poor residents often can’t afford. This, he says, results in a downward spiral. An addict’s incarceration can cause a job loss or eviction from public housing.

In Asher’s view, the term harm reduction has been watered down as the opioid crisis has taken off and more agencies at the city, state and federal level weigh in on what needs to be done. But for Asher it comes down to what he can do on a person-to-person basis, what he can do with this individual in pain right here right now. And often the first step in that is preventing death.

An example of this approach is St. Ann’s Corner’s distribution of fentanyl strip indicators to test for this strong type of opioid, which is increasingly being mixed in with heroin and cocaine. The amount of fentanyl in any given dosage is unknown to the user and unknown to even the dealer. It can be up to 50 times more potent that the opioid found in heroin and is the primary cause of the huge increase in overdoses. Asher educates opioid users about the chemical makeup of their drugs, so they can approach their habits with that much more knowledge.

The fentanyl test strip program represents St. Ann’s Corner’s embrace of “real world working applications,” says Asher, in which established non-profits with a history in the neighborhoods can make a difference. Asher says some other agencies, whether independent non-profits or affiliated with the city health department, can be “complicit” in the very deaths they say they exist to prevent when they do not engage directly with the users or work with them in a program of evidence-based solutions. “We tend to take health concerns and make them moral concerns and that fuels the epidemics and that’s what’s fuel the overdose epidemic,” says Asher. “We stigmatize drug users to believe if you’re using drugs you’re homeless and on the streets, which is not always the case.”

St Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction has been a part of the South Bronx community for 27 years. It was there long before the current opioid crisis and Asher says it plans to be there for the community after the public’s restless attention moves on to the next health crisis. The surge in opioid overdoses started with the over-prescription of legal pain killers in Appalachia, the Midwest, and New England. Through a perfect storm of aggressive pharmaceutical marketing and well-intentioned doctors these highly addictive medications became widespread. For such patients, the pain abated but the addiction never did. The opioids morphed into a deadly combination of fentanyl mixed in with cocaine, crystal meth and counterfeit pills like Xanax and were consumed by the “opioid naïve.”

The users, largely white and often middle class, turned to the street and took their chances on whatever they could find. Deaths soon followed. More powerful heroin became widely available and fed this burgeoning new market of users. In 2015, 10 percent of cocaine overdoses involved fentanyl, up 67 percent. In the last three years, fentanyl-related overdoses are up 540 percent nation-wide.

“It’s largely fentanyl-driven,” says Asher of the increase in overdoses. “It comes from a larger existing perception of drugs being the futile provenance of the throw-away class — once it jumped out of that throw-away class there was an epidemic. More white people are dying and it’s a racist world we live in.”

In a place like the Bronx, in neighborhoods which are served by St. Ann’s Corner, the epidemic is the latest in a line of drug-related crises. Asher notes the swift escalation of the epidemic and that it is unlike the crack and earlier heroin epidemics, which came before.

At St. Ann’s Corner, Asher speaks modestly of the many “reversals” he himself has administered with naloxone. To be there and to help someone escape death makes for a powerful connection between user and lifesaver, he says. “When you save someone’s life, there’s a different relationship” he says. “There’s a level of mutual trust and admiration.” When a life is saved, you’re reclaiming everything that person had or ever will have, he explains. And so Asher continues his work, assembling the kits in their modest blue bags and piles them up in their plastic crates, each one representing a potential life spared.