By Juan Garcia

African American women coping with trauma may find comfort in literature says Sarah Ohmer, author of an upcoming book on healing trauma through works of women writers of the African Diaspora.

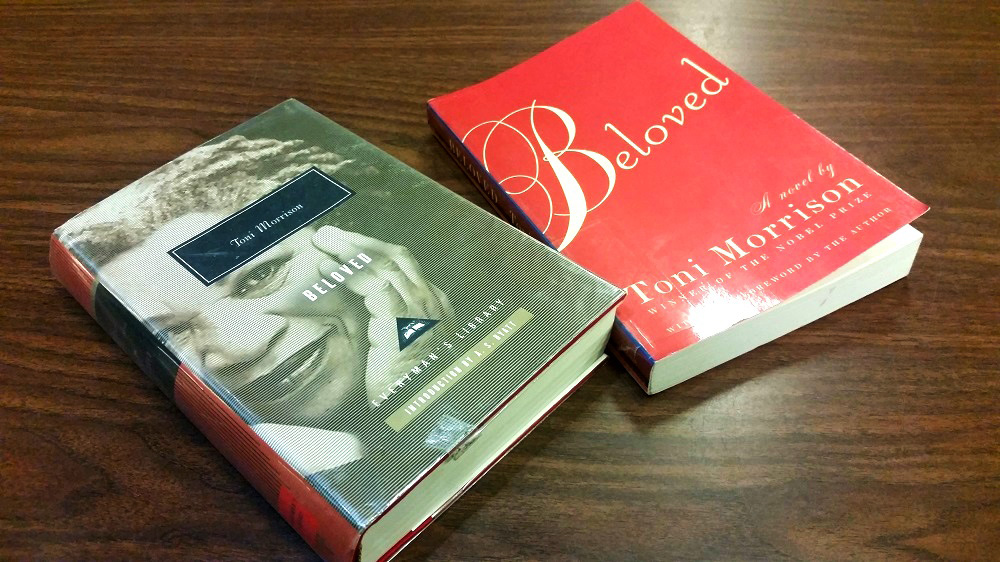

In her book, Ohmer cites texts such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Conceição Evaristo’s Ponciá Vicencio and Maryse Condé’s I, Tituba: Black Witch of Salem. She says that women can learn from the experience of characters like Sethe, a mother of four and a former slave in Beloved.

In a recent reading at Lehman College, where she is an assistant professor of Latin America, Latino, and Puerto Rican Studies, Ohmer explained why. In the story, Sethe takes the life of her youngest daughter, Beloved, because her child was going to be enslaved, a burden she must live with for the rest of her life. She tries to commit suicide but survives. She spends her life repressing what she has done. She is, says Ohmer, a survivor.

In Conceição Evaristo’s Ponciá Vicencio, the main character Ponciá and her brother, both Afro-Brazilians, leave their rural world and go to the city hoping to find better opportunities. They live in the city for years working in meaningless jobs. All they end up finding is disappointment and discrimination.

“When writers present their reader with a traumatic story, the reader serves as a witness,” said Ohmer. “With a witness, possibilities to heal from a personal or collective trauma arise.” Breaking the silence is the first step to overcoming trauma, says Ohmer. Trauma needs to be shared, made visible, by finding someone to listen, a witness, says Ohmer. Trauma, she adds, makes us survivors, warriors and not victims. “Trauma is not just an obstacle,” she says. “It is an open door to access the highest potentials of human existence.”

Ohmer’s book is titled Keloids of Modernity: Trauma and Spirituality in Contemporary Literature by Women of African Diaspora. The keloids, or scars, are the metaphors for the spiritual, emotional, and physical wounds many women of African descent experience, she says.

“There are so many things women have gone through that they haven’t had the chance to express,” said Ava Huggins, a student of African-American Studies, after listening to Ohmer’s reading. “[Her book] is the platform to express their experiences.” As a woman, especially a black woman, Huggins said she feels that Ohmer has done a good job telling the story of women of African descent.

Dominique Winters, an office assistant at the Department of African American Studies, said that Ohmer’s book is relevant because it helps women move forward and heal spiritual scars.

In her quest to learn more about African healing, Ohmer traveled to Bolivia to interview indigenous healers who are called kallawayas and others who go by the name of yatiris. She went to Mexico, looking for communities of African descent and met one or two black women that were also healers in their communities. She met kallawayas who are of African descent and they shared their healing strategies, such as herbs and remedies.

Although she acknowledges that a narrative alone cannot heal an individual, Ohmer proposes an unorthodox approach to cultural interpretation. The narratives presented in her book come from different parts of the Americas and their differences open the door for creative solutions.

The book focuses on women of African descent, but it also can help other people no matter where they come from. “I do believe that any reader can pick up this book and gain something from it,” said Ohmer.

Professor Forrest Colburn agreed and suggested during the reading that Ohmer organize her book to appeal to a wider audience. With a smile on his face, he added that perhaps men should be reading this book more than women.