By Kristopher Charles

When you think of public housing, or “the projects” what comes to mind? Usually it isn’t pretty. The projects are often viewed as black holes in urban society, seemingly suffering from violence, drugs, and poverty. Portrayals in film, television shows, and various news stories keep this view at the forefront of the public consciousness.

One project, however, seeks to change this image. “We The People: The Citizens of NYCHA in Photos + Words” gives brief snippets of people living in public housing. It does not paint a picture of despair, but instead tries to paint one of hope.

This exhibition came about as a result a year of research, and interviews by journalist Rico Washington and photography by Shino Yanagawa. The project aims to “lift the ubiquitous cloak of darkness cast onto the city’s housing projects through candid interviews and photo shoots.”

Washington had the idea for this exhibition when watching the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomyor on C-Span. “How did someone who came from public housing ascend to a nomination for the highest court in the land? That just doesn’t happen and that brings up the conversation of the perceived value of people who come from these neighborhoods. Nothing of value comes from these neighborhoods in the minds of most people,” said Washington.

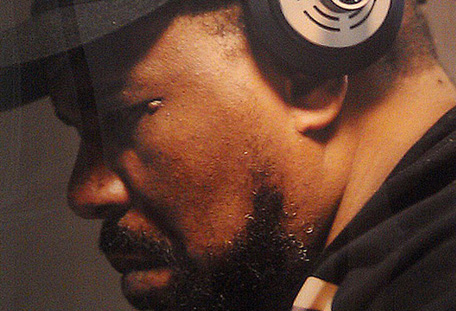

A long list of well known public figures come from public housing such as Associate Justice Sonia Sotomoyor, as well stars such as Jay-Z, Whoopi Goldberg, Luther Vandross, Felipe Luciano, Afrika Bambaataa, and Yasin Bey, aka Mos Def. Luciano, Bambaataa and Mos Def, contributed to the exhibition, their photos and snippets of interviews done with them are displayed alongside those of other current and former residents of NYCHA.

Rico Washington is originally from Washington DC and was also a resident of public housing. His works have appeared in various publications such as OkayPlayer.com, Wax Poetics, Arise and Wax Poetics-Japan. More information can be found on his website: www.superbizzee.com.

Washington said that he knew where he wanted this idea to go, but it all fell to finding someone who would be willing to work on a project like this. “It was difficult, it wasn’t easy,” said Washington as the idea for the exhibition started to become a reality. He spoke to many photographers, many of whom had said this was a good idea, but nothing fruitful was yielded afterwards. “I was like, okay that’s fine, I know that everyone needs to get paid or whatever,” said Washington.

“The universe brought me to Shino. We have two mutual friends in common and so, I won’t say happenstance, I will just say the universe brought us together and I explained to her my idea. It just so happened that she had also wanted to do something of the like, but had not found a mechanism for it,” said Washington.

Washington said that over 50 individuals were interviewed and photographed, but only about half as many were on display, owing to the limited space of the gallery. According to Washington, some of the individuals who had their pictures on display in the gallery had left public housing, while others were still there. He had also said that they had moved on to varying levels of success.

Over the course of the interviews Washington said that a common thread linking all of the people together was a sense of hope. “Their stories echoed hope. It was never ‘I’m here and this is where I’m going to be and there are no opportunities for me and I’m not going to aspire to anything greater than that.’ It was: ‘I was there and I was there for a long time but I knew I was eventually going to leave.’ So you have a situation like Jamal Shabazz, and now he’s a homeowner,” said Washington.

Not only did Yanagawa lend her talents to this exhibition but also some celebrity help allowed the exhibition to take off. “One of our early champions was Daniel Simmons, who is Russell Simmons’ brother, and he owns the Rush Arts Gallery in Chelsea,” said Washington. “He was the first one in that world who said: ‘I get it.’ He was the first one that believed in us.”

In addition to Danny Simmons others lent a hand to make the show happen. A contact within the public housing community acted as a liaison for Washington and Yanagawa for conducting interviews. According to Washington, this man also had an interesting story. However, due to the limited space of the gallery, his photo and excerpt could not be added.

“One specific story that is interesting that comes from Queensbridge Housing as well. He was one the area’s biggest drug dealers for a very long time. Through some soul searching and some epiphanies that came down he decided to get out of that life,” said Washington.

“Now he’s doing a lot of, not necessarily community activism, but he’s a mentor to a lot of the younger kids in the community. He no longer lives there, but he’s still very much a part of the community in that capacity,” said Washington. “He was basically an ambassador to the community, he was the one that brought us in and it’s just remarkable to see how people look up to him now versus how people may of looked up to him back when he was in his prime.”

“He’s self publishing a lot of books, that may be typified as ‘street noire’ or street literature. There are seeds of transcendence within his stories,” said Washington. “This is how this life catches up with and there options for you, there are alternatives for you to not follow this path that can lead you to higher heights.”

This man — Johnny Monroe — was another champion of the project, says Washington. “He’s been of the very few people that have been in constant contact with us. ‘How’s the project going? You guys need any help? If you need some help, I got you. You need to meet this person? You need a little bit of money to help this project come together, let me know.’ He’s been a godsend,” said Washington.

Glenda Pollard, 61, who visited the exhibition had a bit to say about it as well. She lives in public housing. “I was born and raised in the Edenwald projects in the 50s until 1966 when we moved out of there. I heard the interview on the radio and I was interested in seeing the exhibit.”

“In the 50s to me, the projects was a utopia. It was a place of community and it was a place of safety and then in the mid 60’s I think it all changed with the influx of drugs and heroine and things like that,” said Pollard. “The stereotype of being raised in the projects, I didn’t experience that until the mid 60s where people would say their kids can’t play with me because I’m from the projects. But my view of the projects is that it was a wonderful place to grow up in.”

She was surprised to learn that artists like Mos Def were from public housing. “I didn’t know any of these people were from public housing to tell you the truth. Mos Def, or his new name there, I did not know. I knew about Baambaataa, but I didn’t know about a lot of these people,” said Pollard.

The exhibition runs until May 5th and is being held at the Gordon Parks Gallery at the John Cardinal O’Connor Campus of the College of New Rochelle. It is located at 332 east 149th Street in the Bronx. The gallery is open on Fridays from 2-6 pm and on Saturdays from 1-5 pm. An appointment to see the gallery can be made by calling 718-665-1310.