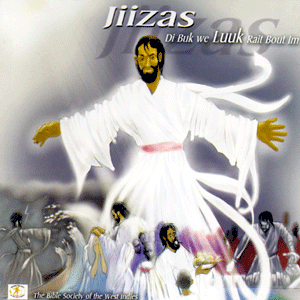

Jiizas: di buuk We Luuk rait bout Im

By Delbert Browne

The Bronx Journal Staff Writer

In December 2011, the Bible was translated into Jamaican Patois for the first time. The translation started with the Book of Luke. The translated title reads “Jiizas: di buuk We Luuk rait bout Im.”

It is primarily an audio project. You can listen to the Book of Luke on iTunes in 24 episodes. Here is the introduction:

Jamaicans who want their native tongue honored as the national language welcome the translation. However, not everyone approves.

Some Jamaicans frown on promoting the Patois, a mix of English and African languages, because they think it is too informal and not “proper.” Others believe it is inappropriate for the Bible and that something may be lost in translation.

Reverend Courtney Stewart, General Secretary of the West Indies Bible Society, who managed the translation project, said in an American Bible Society report that the translated Bible would expand the reach of the church. “Patois has always been regarded as the language to communicate music and folklore, so this is of great significance,” he said. “It means we will be able to communicate the Word of God at a deeper level in churches. And God’s Word will reach people in a way that has previously not been the case.”

The Patois first developed when the British began the large-scale importation of Africans slaves in 1655. Plantation owners and slaves used it to communicate with each other.

There is an ongoing debate over the use of Patois, which is spoken in Jamaica, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Panama and Puerto Rico. Some, as a matter of national pride, support the formalization of its usage in Jamaican society, while others say it undermines the credibility of the speakers.

Patois is generally viewed as a “poor man’s language” in Jamaica. It includes English words, but does not follow standard grammatical rules. It is mainly a spoken language and is not usually formally written.

In New York City communities like Crown Heights, Wakefield and Queens Village, Patois blares from stores and is called out from cars. “Wah gwan, bredren? (What’s up, brother?)” In restaurants, customers order chicken with a side of steamed cabbage, “Me wan di jerk chicken, widda side of cabbage, stiimed.”

Second generation Jamaican Americans often do not master the Patois because immigrant parents do not encourage it and it is not taught, or even allowed, in American schools.

Jamaican American Christine Turner, a resident of the White Plains Road area, says the translation is a foolish idea and that it will be a “task” for the people working on the project.

“We (Jamaicans) are not accustomed to reading in Patois. It takes me a longer time to read,” she says. “It is easier to speak, harder to write.” Turner, who hails from West Moreland, Jamaica, believes Patois is also highly variable and differs by parish. “For instance, in St. Elizabeth, when they speak Patois, I can’t even understand everything they are saying. So their interpretation of the Patois is different from my parish.”

Translations can vary not only in speech, she says, but also in spelling. Turner offers to translate a sample, Holy Bible, King James’ Version, Psalm 18:6.

Turner recalls her upbringing, where her elder family members were always reminding her to “speak properly,” especially if they were from the United Kingdom.

Jullette Sanchez, a Jamaican American English professor at Lehman College, says a Patois Bible is harmless. “It is a local language that people hold dear,” she says. “Who are we offending when we translate this text . . . why would this set us back?”