By Basilisa Alonso

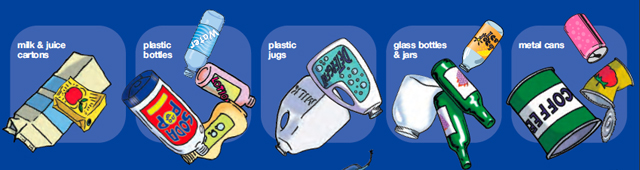

Herman Rivera, limping, pushes a cart filled with an assortment of plastic, glass and, metal cans and bottles along Manhattan’s 125th street to the can deposits in the back of a Pathmark grocery store. His few belongings share the cart with the bottles and cans.

One of his most cherished possessions is a royal blue sweatshirt. It is gently placed, along the front seat of the worn out grocery cart, carefully secured like the toddlers that once occupied it. The solid vibrant sweater, a pole and a Mexican ID is all that remains of his sole companion, his brother: Juan Hernandez Guerro.

His wife abandoned him and his only relative, Juan, his older brother, is gone. He said they would collect cans together but it has been weeks since he’s last seen him.

Hernandez-Guerro was arrested two weeks ago as he was walking with Rivera to the can deposits. Rivera contends a police car pulled up to the curb, an officer got out and put handcuffs on his brother. Rivera said he was desperately trying to ask the police why they were taking away his big brother. “ ‘Hey, you move!’ was the only answer they gave me,” Rivera said in broken English. “They took him away, without explanations.”

Fighting back tears, he said, “All I want to know is why he got arrested and where my brother is. They [the police] have more compassion for an animal.”

A media representative for the New York City Police Department declined to comment stating, “We have other more important media concerns going on.”

In 2010, there were about 39,000 homeless people in New York City registered with municipal shelters, according to a report by the New York City Coalition for the Homeless. Being homeless is daunting enough but being homeless, undocumented and disabled is even more so. Approximately 90 percent of homeless New Yorkers are black or Latino, according to a 2003 report by the same organization.

Ainsworth Ferril, 26, an on-site maintenance worker at the 125th street can deposit center, is a witness to the growing numbers of the homeless. He works for TOMRA , the recycling company, who along with the Pathmark grocery store, own the center.

(Dandeluca)

Ferril sympathizes with undocumented can collectors like Rivera. He says some of them collect cans because they need help make “ends meet.”

Ferril says these people are also “picked on” by the New York City Department of Sanitation along with the police department. Encounters with these two city agencies can be heartbreaking, he says.

Ferril believes the police target vulnerable people who do not have a say in the community, making them susceptible to abuse.

The cans and bottles that oftentimes litter streets and over flow trash cans are valuable not only for the can collectors, but also for the sanitation department. Ferril says that the department “uses the same material to make a profit.” So when the can collectors dig through trash they are “stealing public property.” Often, Ferril contends, sanitation workers throw out the carts that belong to the collectors because they are deemed as “trash.”

“They have their whole life on those carts,” Ferril observes. “The few belongings they have in this world.”

The sanitation department responded to an email saying, “The Department has no record of these allegations.”

Police also “bully them,” Ferril charges. Unfortunately, he adds, “Police harass can collectors pretty often. Undocumented collectors are definitely a target for the police — who better to give a ticket to than these people?”

“I don’t know if it’s a quota they have to fill,” he says, “but these people are just trying to eat and survive.”

An NYPD sergeant, who wishes to remain anonymous and who has been working for the police department for eight years says, “I have never seen a police officer ‘harass’ someone unnecessarily or because they thought they were undocumented.” The sergeant denies any existence of a “quota” system, but acknowledges that “there are expectations on officers to produce activity depending on the assignment.”

A few months ago, Ferril says a police car parked on the street where a Hispanic can collector was waiting to deposit his cans. After the man finished, Ferril says that a police officer arrested the can collector for possession of stolen property: a BJ’s shopping cart. To Ferril, it didn’t make sense. “Even though the shopping cart was stolen so is everyone else’s,” he said.

In another instance, Ferril says he saw a man arrested while he was separating his cans. The collector was holding a beer can and then set it aside next to him. Ferril says what happened next was absurd: “They [the police] arrested this guy because they said he had an open alcoholic container.”

Those two instances stand out in his mind, he says, because they are instances in which the people who are supposed to protect civilians, are abusing their power and picking on those who are down. “You don’t see them arresting ‘normal’ looking people,” or at least not with the same frequency and not over incidents like those, he points out.

Now, Rivera spends his days alone, scouring, the city for cans and bottles. “Sometimes I get a lot and sometimes I get nothing at all,” he says.

At 33, Rivera’s youth is enviable by many other undocumented workers who are aging, limiting their time as “jornaleros.” They can only dream of regaining their youth. Rivera, however, is worn out and tired. Some days he begins as early as 3 a.m. stopping only when there is no more space left in his cart. He then makes his way to the deposits and afterwards, he goes out again to look for more cans.

“On good days, I can make $20 maybe $30,” Rivera says.

Rivera who came to the United States almost 20 years ago, worked in construction until he suffered an on-the-job accident about two years ago. He fell down a ladder carrying construction material. As a result, his right knee is now permanently damaged, causing a limp in his walk, and he is unable to work in construction.

Rivera said he spoke to a lawyer. “He told me they couldn’t do anything about it. The hospital costs came out of my pocket, my savings.”

Before his accident, he worked for nearly 20 years. During that time, he made about $400 working five days a week in construction and doing textile work. Now he barely makes $100.

But Rivera still manages to send the little money he collects back to Mexico to help his eight brothers and sisters. His family, however, do not know that he is unemployed and homeless. “They don’t know because if they d,id they’ll worry,” says a resigned Rivera.

Getting help can be hard, he explains. He tried reaching out to a South Bronx organization but they turned him away when he went there. “When I went they told me, ‘come back tomorrow.’ Without money how am I going to go back?”

He doesn’t plan to go back to Mexico anytime soon. His dream was to “have a house to live in,” but without a house “what am I going back to?” he asks.

Can collecting can be a dangerous occupation. On one occasion Rivera said a man tried to take a pole from his cart, which was used to hang his bags on. The man tried to take it to beat me up with it. The pole broke and he grabbed the other end of it. “I wasn’t scared,” he recalls. “I felt like I had to defend myself.” Luckily, he was unharmed.

Unfortunately he had a worse fate when he was attacked on Park Avenue in East Harlem. Three teenagers broke his nose bridge and beat him until “they got tired,” he says. He was left lying in a puddle of his own blood on the street until a good Samaritan called the police. He doesn’t know why he was brutally attacked or if the assailants were even caught. “I think they just did it because they felt like it,” he says. He was in the hospital for almost three months. He had to get multiple stitches and now has a lifeless lid covering half his eye.

Ferril, the deposit center maintenance worker, expresses compassion for these homeless men. He says people who interact with the can collectors can be cruel. Some parents tell their children, “hold your nose” and “don’t get to close to them” as if they had a disease.

Teenagers on summer vacation can be downright vicious, sometimes throwing rocks at those who are in line.

“They do it,” Ferril says. “I don’t know, maybe because they are bored.” Nowadays, Ferril says, “You can’t even treat animals that way. So why is it okay to treat human beings in such a way?”